Q&A with Sara Carlsen

A documentary filmmaker based in Brooklyn, NY.

Sara Carlsen (she/they), 26 years old, is a documentary filmmaker based in Brooklyn, NY. Originally from Kansas City, Carlsen moved to Brooklyn in 2022 after studying film at the University of Kansas. They have produced, edited, and animated multiple feature-length documentaries, and—among other projects—are currently directing a short doc centered around miracles based in Missouri.

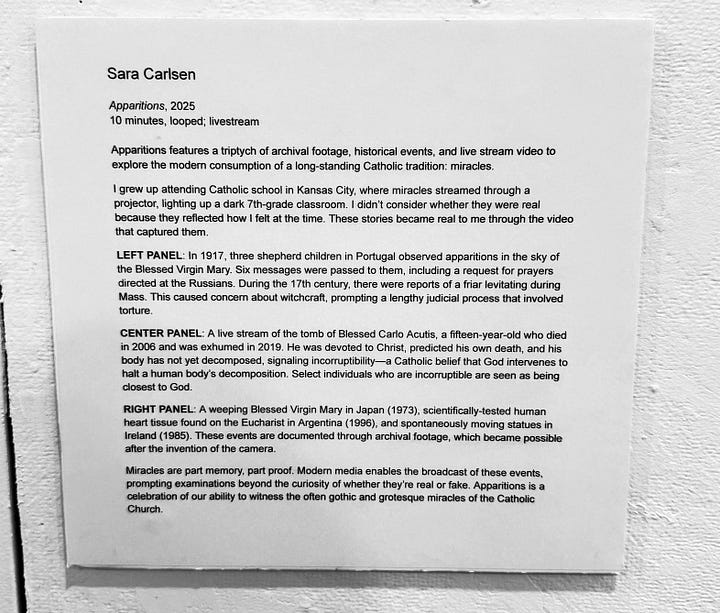

In addition to being a documentary filmmaker, Carlsen helps to run Verdant, a Brooklyn and Queens-based artist collective that gives local creatives not only a place to present their work, but the help to progress their art. They most recently had a gallery show titled CONSUMED//EXHUMED, where Carlsen showcased a piece titled Apparitions.

Carlsen is not only a talented and passionate creative, filmmaker, and Midwest advocate, but they are also a genuinely kind person. We met up near one of our most-frequented locations, Syndicated movie theater, so that I could learn more about their background as a documentary filmmaker, their most recent projects, and life as a creative.

Could you tell me about your background in film, and when that interest started?

I feel like it's been something that's been consistent in my life, but I didn't realize it was something I really could do until a friend was like, “You should go to film school,” and it sounded so ridiculous, but it kind of started to set in as something I actually did want to do. But it felt unattainable, obviously, growing up in Kansas, and then education wise, there are less options.

So KU (University of Kansas) had a film school, and I didn't know what I wanted to do [ . . .] But then I attended True/False Film Festival through KU, and they paid for the pass and sent us and introduced us, and it's a full documentary film festival. So I got like 10 docs in one weekend, and I was like, this is what it's all about. This is fitting, because it felt like it honored this interest in history I have, and it also honored journalism things I enjoy, and it also honored film and had this artfulness around it. It comes in a specific vision and package, and the work involved in creating that is very personal and true, inherently.

And so after going to True/False, I knew I wanted to do it, so I've been to that film festival ever since. I've gone nine years now, because it just feels like it's reinvigorating. And then, and at that point, I kind of started to pursue a documentary route, because that was the most exciting thing to me, and I've been doing that ever since.

What was the transition like from studying film at KU to moving to New York?

I think in some ways, relationships with professors helped a lot connecting me to places I wanted to be at, and also gave me some kind of realistic view of what this is like. Because… there's commercial elements to [film], like there's money around it, and investors and grants and all of that is so much broader, and I feel like it's been a lot of work to just internally maintain a vision while still trying to get enough money to continue working. That's just always the tension: I know what I want to make, I know how to make it, and I know what I need, but the connective tissue there is inherently money. You just truly need storage, you need a camera, and you need gas and gas money.

So it's been kind of looking around and looking more so for people who share something with me, and an interest and excitement and passion towards telling a story, and seeing what we each can bring to create something [. . .] It doesn’t have to be my exact interest anymore. It's like, how can we combine interests and create something unique with them.

So going from KU to the five years that have passed, I feel like my excitement is the same [. . .] I have a narrowing focus I feel like, and knowing what I'm able to do in a day, I feel like I have a better sense of that, actually having the experience.

You work on documentaries for your day job, and then you also have your own personal projects that you’re working on. How do those two work together, or even in conflict?

It’s interesting because, within a week, I'll be working on a super localized community project that's absolutely for free. I'll be working on commercial work that's for clients, like a feature length documentary I have to finish in three months, and then also a large-scale production that's going to HBO in like a year and a half. So the amount of time is so different between those things, but your energy has to be there for all of them.

So I feel like a lot of it, and I feel this is true of art in general, you have to schedule it, art has to be scheduled. And I'm serious about that, there's so many things I want to be doing, but, Tuesday nights, I'm on this one project, and that's what I'm on. Fridays, I only spend time on this one thing, and then scheduling time in on the weekends to do personal things that hopefully you develop into being a weekly thing, you hope to get to that point.

But I really like getting to be in these different worlds every day, because it makes me better understand what I want to build in a team. Because I want to direct one day, and I see failures in direction, I see successes in direction in such different scales of projects. And I think that all helps better train me in a way that school couldn't for what I want my team to look like.

For someone who hasn’t seen it, could you tell me a bit about the piece you displayed at the most recent Verdant show? Could you walk me through the inspiration behind it, and how you created it?

Well, it started with a TV I found because I wanted to show something in an art gallery that had documentary elements, but I was asking myself, “How do you do that without giving the audience the full context?” Because I'm so used to the three act structure, and I feel like, if you're in a gallery, it's so brief and it's so kind of temporary, that I needed to build something that looped and also regenerated a little bit each time you're looking at it.

I had already been doing research on incorruptibles in the Catholic Church, because I grew up Catholic, and the idea of incorruptibility is that somebody's decomposition is halted by God because they're considered to be particularly spiritual. So I'm already doing a project about a miracle in Missouri that has to do with a nun being an incorruptible, and in thinking about that, I kind of moved a little bit more towards Catholic miracles in general. And I thought about the media I was shown in Catholic school growing up, and how, and I think about it often already inherently, how visceral that was, and how it just felt so unique. Instead of reading out of a textbook, you're being shown arguably archival footage of miracles occurring, and this just felt so deeply to me like proof. Like inherently, having a camera pointed at something means that it's true [. . .] And it felt like, you know, things are so volatile when you're a kid too, and there's so many things you're learning all at the same time, just inherently in life that that volatility leads to you wanting to grasp onto something [. . .] And when I thought more about Catholic miracles, I thought about media I was shown, both historical portrayals of these films we would watch in class and archival footage of these miracles actually occurring.

I wanted it to feel as present as possible, I wanted people watching it to feel like they're also witnessing, a little bit through a childlike lens. So I wrapped it all in this live stream of an incorruptible, the tomb of Carlos Acutis, and nothing is happening in that live stream in the center, except just the moment in that tomb in Italy. But on the left and the right are these two panels where these looped videos of miracles are sort of interacting with each other, surrounding this tomb.

And I wanted to create that three panel structure, because… at True/False I saw documentaries that had this multiple-screens-at-once structure that I think compels audiences of today more because of social media, and because we're scrolling so quickly. One shot on screen isn't enough almost, and so sort of berating audiences with these miracles hopefully gives some larger scale and depth, both a deep and wide perspective, of Catholic miracles and what those might look like. And so Apparitions felt like the right title for it, because displayed in the center is a live view count of the live stream, and it feels like the idea of other people watching this live stream is sort of also like an apparition. This number is shifting and changing, and us watching is adding to that number, so we're an idea to other people. And I think the idea that children in Catholic schools across the world are being shown the same thing, you're all sort of collectively believing, and I like that idea.

You explored religious themes in that piece, and are working on your miracle-based project in Kansas City. Are there any consistent stories or ideas that you’re really drawn to?

Maybe this is too honest, but it's encouraged for people to work on stories about their own background, because that's what you know best. So I started to think about things that linger with me as an adult from my background, and I think it's growing up in the Midwest, it's being Catholic, it's my background and other things as well. And I think there are parts of the Midwest that will pass you by if you don't look closer.

You’re always looking for, in documentary, for tension, and you're looking for complexity in something [. . .] So I feel like, when it comes to the Midwest, where I come from, there's a lot of things that people just pass by that have more complexity around them. So I feel like the stories I tend to pursue have larger historical context and a modern day implication around that history. And I think for this incorruptible story, the way that traditionalism and reformist views of the Catholic Church have played out are kind of embodied in this story.

So trying to connect some complexity to something that might be understood quickly is what makes for a good documentary. Like, there's something that people walk out of it feeling like they got to see a unique perspective on something true. Because there's a way to just look at a Wikipedia article and read something and you leave learning something. But I think documentary specifically is wrapped in that artistic vision that takes pursuing characters and a story and a narrative, and having those visuals, that makes for a good documentary. So I think that is the tie that connects me with work that excites me.

Could you tell me a bit about Verdant, and what it’s been like to have that community space?

I think the goal of Verdant, to me, is to create a structure for artists, to enable artists to create more work. I think we all have this voice in our head that's like, I'm not this thing because I have to do blank thing in order to actually be that. And I so live by the idea that the way to become the thing is to believe you are the thing, and the way to get into an art show is to submit to an art show, the way to submit to an art show is to create art, the way to create art is to have a deadline. And I truly believe that Verdant, it does this thing so well, of just creating deadlines for artists to ensure that they are completing something, and encourage that and assist and collaborate and help and answer questions or provide advice… whatever it is, just being that open space to express even your fears or questions, or just have that safety and community that is gonna ensure that your ability to create art is protected and sustained [. . .] That's the goal of Verdant, to me, is to be this machinery that fuels artists’ ability to create work, because sometimes that looks like really boring logistical stuff of emailing and scheduling and money, and we want to help with all of that.

Want to check out more of Sara’s work? Refer to their website, and follow Verdant’s Instagram to learn more about upcoming events and opportunities.

Want to be featured in Marcescent’s next Q&A? Reach out to marcescentzine@gmail.com.

Amazing interview!!

LOVEEEEE