Fossils

Issue 01: Summer 2024

A Special Thanks to Our Contributors:

in order of appearance

Maddie Potocnik - Cover Design

Dearest reader,

Thank you for being a part of our story, and allowing us to be a part of yours. Marcescent is a communal space of sharing and reflecting as a means of connection and furthered understanding. With the theme of Fossils, we have chosen to showcase work that deals with the subject of un-surfacing, of looking back through the records to find the answers to our current questions.

As collectors—of stories, of stones, of pictures—we find a special resonance in the idea of looking back to look forward. The universe is old, much older than any one of us, and everywhere we look there is more than we will ever see. As such, we reach back in attempt to reconnect ourself with all that has come before, to the grand narrative of existence; and if you listen, there are whispers all around.

In the future, say there are no gloved hands to drag these words from the rubble, and wonder about the dried flowers we saved, the libraries collected, the medals and tickets and photo strips tucked in tattered boxes. Even if our fossils are never to be found, what a privilege it is to be a depository of time, to be a portrait of change.

Certainly, it is a privilege to share this moment in time with you.

With love,

Co-Editors in Chief

Colton Trowbridge (Writing/Editing)

Ellen Rice (Art Direction)

There’s a Tree

Alexandria Buss

There’s a tree I used to climb as a kid

Big old man

Strong and sturdy

He lives just a minute’s walk away from my childhood home

Still lives there

I think about him often, how old he is

How long he has until he fossilizes

In a way, he exists to me as a personal relic

A distant memory, I branded him with my initials

I cried to him, laughed with him

He saved me from falling out of him

The country woods in Kansas are eerie but he was safety

And he still lives exactly where I left him

And I’m missing him so much right now

But that doesn’t mean he’s gone

quarterlife

Pet Hall

windows out the window

watch a cold cup of tea

light seeps the sill

tucks the sheets into me

frames and clothes

still alseep on the floor

ungiven gift

stay a sight for the sore

carved the years

somewhere in the sand

kissed the sea

with closed lips of the land

a coat too thin

for a winter this cold

the harder the hand

the less all unfolds

Sunlight Through the Window onto the Couch and Over the Bodies

Chloé Ryan

I am comfortable

Your body against mine and I am comfortable

Delicious delicious comfort

I never thought I’d call comfort delicious

I feel sexiest when I am safe

tick tick boom

the clock hits noon

I am still in your arms

laziness passed out on the couch last night

too drunk or high on something in the air to make it home and has yet

to wake up and leave

Smeeling off the Peelings

Chloé Ryan

Smeeling off the peelings

Peeling off the schmeelings

Is this the first time

Water skin clothes peeling off so the feelings can fit in

Only room left in between for things that exist inside us

Is it time?

Reeling from the feelings

Peeling off the feelings so the clothes can fit in

Did you know it was the last time?

DYING TO KEEP FOSSILS ALIVE

Trevor Bashaw

“Language is fossil poetry. As the limestone of the continent consists of infinite masses of the shells of animalcules, so language is made up of images, or tropes, which now, in their secondary use, have long ceased to remind us of their poetic origin.” - Ralph Waldo Emerson

now in the mouth of the page

take the stench of a deep breath

tooth-splint fondling keys in my pocket

staring at the solar flare

or is it an optical illusion

scrubbing my brain

with steel wool

can we remove the sky?

then all of the color blue?

then zipline into that nothingness—

it could be like a reward

for doing things as fast and big as possible

Even dying

The smell of a retirement home

School cafeteria warm like a canned spaghetti remnant

licked in a dirty tin pot

My electric shaver lost wifi signal

So the stubble will remain

Study jellyfish

They are portals

With halos

Gulping like radial eels

A sea jelly like a star is a ring pulsing

blue on the inside and on the outside

it is an eye / the sun too is an eye — one catches light and one emits it

Light alone shaped them — into whatever it is they are

All night i could stay up like this — Lucubrating

Lubing up my locomotive loosh factory

Almost like an alien’s pet fossil fuel

Only almost because suffering is renewable

The matrix is a womb

The matrix is a mother

It simply that which gives origin

Until the truth is ready

TROVE

Trevor Bashaw

We must rectify the profits

Of this faceted bodega

Abdomen surfactant

Boutique facsimile

Factory mollification

Dignity confetti

Doom confetti

Prosthesis fetish

Promethean sconce

Forfeit a thesis

Fictive orifice

Petrified affection

Houses Of Memory

Colton Trowbridge

“Even if you were in prison, with the walls of your cell keeping out all the sounds of the world, wouldn’t you still have your childhood, that priceless royal abundance, that treasure-house of memories? Look there.” - Rainer Maria Rilke

I live in houses of memory, smoothed back by time. Often, in conversation with my twin sister, Carson, I find that two people who experienced the exact same people and places at the exact same time have wildly different memories, or no memories to speak of, for seemingly significant places and events. Time acts as an ocean, pushing and pulling back once sharp, clear memories over and over until all that is left is something soft and clouded. And yet, in many cases, memory is the only record that remains. So what do we make of the spaces created in memories? Spaces that may be far from reality, yet now exist solely through the lens of sea glass. To explore this, I returned to the memories I had created of our family home in Kansas.

My family doesn’t move around. My parents have lived in the same house for my entire life, and I too lived there for my first eighteen years. I can return to the house whenever I like. In this way, it exists not just in my memory, but in a reality that can still be checked against the record.

Though, while it is the same house, each summer my mom takes on a new project. Painting the interior walls a new color, changing the layout of the living room, the theme of the kitchen, every few years a new piece of furniture or porch decorations, and on occasion, when another grandchild was born or family moved home or away, a complete change in the function of a room.

As a child, I remember the small basement room closest to the stairs held the family computer, an old bookshelf that I never once saw a book removed or replaced from, and a filing cabinet that only my dad knew how to navigate. The two basement bedrooms belonged to my older sisters, with my parents upstairs in the masters and my twin sister and I in the remaining two rooms. Of these, only my parents’ remains the same.

When I went away to college, my mom sent me pictures of my room reorganized with new artwork on the walls. Pictures and posters of the directors and films I had loved while in high school. As if to say, I still remember you. I am thinking of you and holding space for your return. It touched me. Her nest was empty for the first time in thirty years and the bedrooms must have seemed so quiet.

I imagine her each day, walking past the space I had filled with so much junk. The organized chaos I picked up from Dad. Never throwing anything away. A fine line between collecting and hoarding. The room where my music constantly played, now silent and clean. It must have felt so wrong. I think my mom’s redecorating of a room I no longer occupied was a way of keeping her memory of me sharp. In some sense, an attempt to slow the erosion of time. I will never be the little boy that used to share that room with his sister, or the middle schooler first falling in love with film, or the teenager first exploring my tastes, but she had the ability to hold all of that in a sort of stasis through fixing those parts of me to the walls. In this way, our memories intertwine to create a sort of amalgamation of my character through my childhood room.

Our family home has gone through three major renovations. I find it in three different memories.

—

I visit the first of my homes of memory and see red brick and white wood siding with green trim. Always, there is a green, meticulously mowed lawn. A long driveway. Two trees, a crabapple just outside the dining room, and a paperbark maple outside my bedroom window. By the corner of the driveway, near the street, there is an evergreen hedge, just beside the drainage overflow cover. Where the driveway stops its slope and continues level into the garage I see a basketball hoop, with soft, round edges framing the backboard. Across the driveway, sits a tall patch of Maiden Grass, a sharp ornamental grass that would sometimes cut my hands when I reached in to grab a lost ball. There are two more evergreen hedges in the small garden around the crabapple tree, and another two in the front of the house, who would grow red berries each spring.

I look up my address on google maps and find a photo of the house from August of 2007. Most of what I remember from this first version of the house is correct. There are the two large trees, the red bricks, white siding, and green trim, but there are also two large evergreen hedges, on either side of the basketball hoop. I vividly remember the hoop. Down to the size and shape and coloring. It is exactly how I pictured it, and yet, here are these two massive hedges, larger than any of those that I had remembered. And even with photographic proof, I cannot find them in visiting my memory house.

I ask Carson about this. She remembers the color of the trim, and the trees.

I have no recollection of the hedges.

And she asks me about the backyard, of which I have no photos. As we walk through the yard we see the side garden where our parents grew tomatoes and okra and other vegetables, and the red brick and concrete retaining wall, and the trampoline, but then we reach a void. A space in the yard falls away where our memories don’t align, or cease to exist at all. At some point there was a playhouse, complete with a green slide, climbing wall, and swingset. When I visit the house alone, I see it exactly like this. But Carson doesn’t.

What was here before the playhouse?

Certainly

something.

Vaguely,

we start to see

a sandbox

appear,

filling in a corner of the void,

a wood border is propped up to hold the sand in,

and grass begins to grow around the edges, so that now the void is completely filled out. So we have created a memory, which very well may be true, but now is there, either way.

Later, I visit the house again, this time alone, and find that the sandbox still stands where the playhouse once was. I take my shoes and socks off and feel the first sting of the hot sand in the summertime, and as I dig my toes in, the coolness beneath. I have a feeling though that I need to be careful, that while I cannot see the playhouse, it is still there. And indeed I catch flashes of it. Out of the corner of my eye, I catch Carson climbing across the monkeybars and standing up, holding on to the lowest branches of the neighbor’s tree, which stretched across the border of the fence. And then she is gone, along with the playhouse, and I am digging into the sand and ripping through the black landscaping cloth to the clay underneath. My hands are small, the same size as Carson’s as she reached into the tree. I am definitely still at the same house, and yet both of these spaces exist, and I am unsure of which is reality.

Approaching this second house, I see red brick and taupe wood siding with white trim. Still, a green, meticulously mowed lawn. A long driveway and a large paperbark maple outside my bedroom window. Underneath it, sparrows and chickadees preen in a birdbath shaped like an angel. There is a new basketball hoop, cemented into the ground and raised high, with a tattered net hanging loose from wear. Where once the crabapple stood, a wood chip garden, decorated by a rickety wooden bench and flower pots and a pair of antique toad statues, soaks in the sun. The sharp bush in the corner is still there, but the hedge at the end of the lawn is gone.

I don’t remember when or how the hedges were taken out. I never remember a stump, or bare patch of ground in the lawn that my dad has always been very particular about, but at some point there must have been. The new basketball hoop I remember. I helped mix the concrete and dig the hole. However, though I clearly see the new paint job on the house, I cannot for the life of me recall the process of it being painted. Certainly this would have taken some time and a fair bit of space, but I don’t have that memory. Simply, it was white and now it is brown. I do remember when a new family moved into the house on the corner of the culdesac, and immediately painted the outside a bright canary yellow. I remember too, when the neighbors next door decided to paint their house green, though hadn’t landed on an exact shade yet, and so painted several swatch tests on the face of the house, then left those strips of varied green up for weeks before finally painting the whole thing. When I think back, I can remember neighbors on either side painting their houses, as well as those across the street, and yet I have no recollection of our own.

The removal of the crabapple tree is a different story. I clearly remember its demise. One summer, when I was still in elementary school, a swarm of bees took up in the tree in the middle of a sunny day. I had been collecting tadpoles from a local creek, and was afraid that the bees would attack them, and so hid in the garage before alerting my parents. The solution was simple: call someone to remove the bees, and cut down the tree. And I was heartbroken that they had made that decision. In one fell swoop, in the course of an afternoon, the bees had taken away my favorite climbing tree.

But that isn’t how it went at all. I ask my parents to confirm the details and they tell me that there was a swarm of bees that briefly took up in the crabapple tree, but that by time the beekeeper arrived to remove them, they had already moved on. All that was left was the waxy residue of the beginning of a hive, which the beekeeper removed.

And that was that. The tree was still there for quite some time before it simply became too big for the space. It had been planted without due planning for how large it would grow, and was causing damage to the gutters and would continue to encroach on the roof and side walls if it wasn’t removed. Dad and his best friend Brian cut it down, though both my parents agree that it was sad to see it go. Unlike the hedges in the front yard, to this day, there is still the scar of the tree stump in the garden. When I visit I like to sit next to it and remember what once was.

—

Approaching the last of these memory houses, I see it more or less how it stands in reality today. The brick has been painted over white, to match the siding, and the trim, along with the garage and a triangle at the peak of the face, are black. Mom has added flower boxes and decorative shutters to windows, and the maiden grass has been cut down. The yard is still cut short and brilliant green, as Dad would never have it any other way. The basketball goal is gone. Dad backed into it with a U-Haul years ago, and finally they decided the half crooked goal was more a hazard than a benefit, and took it down. There are two faux-rock urns beneath my bedroom window, where the ashes of our family dogs sit in the sun. Mom put them there so they could be close to me, and it helps me connect to them in memory.

In the backyard there are still the ruts along the fenceline where they would run back and forth, barking at anyone who dared walk along the sidewalk to the little park commons. The play-place is still there, but has certainly seen better days. The trampoline and garden are long gone, but otherwise it is exactly the same. The slopes still remain, and the retaining walls, and vinca garden. The rock pathway from the front yard to the play-place is still there too. It covers the scars from my years of digging as a child.

Though this is the most ‘real’ of the houses—it is there now and I can return and check each memory with my own eyes—it is somehow the least real to me. The painting and removal of the basketball goal and maiden grass all came after my move to Lawrence for college. In that time, my room became briefly not my room, and when I visited I slept in the guest bedroom downstairs, and one Christmas on the basement couch.

When I visit home this is the house I return to, and it is real and familiar and home, but when I am away and close my eyes I see red brick and taupe and white walls, and a basketball goal. I see Carson’s car out front, near mine, and the garage door open. I hear the clickety clack of Winnie and Duke scrambling across the wood floors to greet whoever has come to see them. I hear the TV in my parents room, though I am as likely to find my nieces, or an empty room, as I am to find my mom. In my mind I still hear her sitting in the rocking chair by the window, talking on the phone for hours with her best friend, Stephanie, or Nana. Dad is asleep in the living room, listening to an audiobook, or outside mowing the lawn. Always, it is summertime when I visit, and the cicadas are droning and the air is sticky and thick and there is a soft breeze if any at all. Carson is downstairs on the couch, waiting for me to join, and my room is my room.

—

In April of my freshman year at college I decided to tell my parents I was coming home for my birthday a day later than I actually was, so I could spend a day with my long distance girlfriend. At the time, I saw it as politeness, so that they didn’t feel like I had chosen her over them. That night, in her dorm room, I got a call from my mom. She told me that she was sorry and wouldn’t be seeing Carson or I the next day for our birthday, that she and Dad were getting in the car for Texas. Papa, her daddy, had been sick for a long time. His hospice nurse had called and said they’d better hurry down if they wanted to say goodbye.

I received this news in a dorm room twenty minutes away from our house, pretending to be hours away at college. Mom’s daddy was dying and I could have been there to comfort her in that moment, but I wasn’t, and the first thing she thought to do was apologize to me.

The next morning, I made the short drive across town to my parents house. All my sisters were there. My brother in law made us frozen margaritas and we drank them on the back porch and tried to make light of the situation. It was the first time Carson and I hadn’t seen our parents on our birthday.

We woke the next morning to messages from Mom saying Papa had slept the whole night through for the first time in years. He passed around midday. It was Easter.

Papa’s celebration of life was held that June in Wimberley, Texas, at the little church in town where Nana and Papa were both well known. Both of my grandparents were close to Reverend Clint and he fought back tears throughout the service. They played the video I had worked on all summer with Mom. A slideshow of Papa’s life with his children’s voices and his favorite songs. I had seen the video countless times over the months between his death and service, and afterwards had to remove it from my laptop and place it on a hard drive so I wouldn’t be reminded. I had ripped the music from iTunes, something I know my Uncle would have disapproved of, and deleted the songs from my account as well. I still think of that summer any time I hear Don Williams.

I didn’t realize then, but that would be the last time I ever saw my grandparents home in Wimberley. Fittingly enough, the street they lived on is named Memory Lane. Theirs was the last house on the street. Following the service, we spent a few more days with family in Texas, and then drove home, bringing Nana with us. Nobody wanted her to be alone. She stayed with us for several weeks that summer before flying home with my father as a chaperone.

Soon after, we began to receive updates from my uncle in Austin, that Nana wasn’t acting quite herself. She was spacey in conversation, frequently forgot to feed her dog, Tess, and take her out to potty, so Uncle Craig had to clean the carpet many times, and despite that fact that she had made the drive from Wimberley to Austin countless times, she became disoriented even with a GPS guiding her.

One evening, on the way home from visiting my aunt and uncle, Nana got lost and somehow decided to make a turn onto train tracks. Her car got stuck, and luckily, workers noticed and were able to free the car and help her on her way. I can’t imagine what may have happened that night had there been no one else around. Neither could the rest of the family.

Mom and Uncle Craig decided it was time to take her keys away, and look more seriously into her mental state. Her doctor at the time had said it was possible this was all a form of grieving, and that sometimes this happened after the loss of a spouse, and the fog may eventually clear. Mom had been frustrated by this for some time. It was increasingly evident to her that this was not the case, and she had to push for the reality to be seen.

In June of 2021, Nana was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. By the end of that summer the decision was made to move her from her home in Wimberley to live with my parents in Kansas. Tess, her yellow lab, was eleven by then, and though it was a hard decision to make, Mom and Uncle Craig thought it would be best if she stayed in Austin. She was old and overweight, and they had labs of their own who she was already close with. Tess passed last October, the last in the line of labs Nana and Papa had owned throughout their lives together. She received the most benefit of their old age. Though she was incredibly well trained, she was allowed to sleep on their bed, and Papa often fed her scraps from the table, something he would have never dreamed of allowing with any of the others. I can just imagine Joe and Rowdy and Ella watching on in disbelief from the kitchen doorway, incredulous at the lack of shame in that big happy dog begging with her chin on Papa’s skinny legs.

I don’t believe my Nana knows that Tess is gone. I hope, in the midst of all the horrors that Alzheimer’s has wrought, she’s been offered at least this one kindness.

In Kansas, my parents moved Nana into what had been my room. The clothes I left in the closest were moved to bins in the basement, my old dresser drawers similarly cleared out. The posters and decor on the walls were taken down and replaced with photos of Nana and Papa, and Nana’s family. Papa’s old roll top desk was placed in the corner of the room, and is filled with letters and mementoes of his, and their, life. Even the bedsheets and pillows were changed. The only part of the room that was never changed were the closest doors.

In high school, Mom had painted them in black chalkboard paint, and friends and I drew pictures and wrote stories. All these years forward, these stories and drawings still remain. Scrawled across the top of the doors is my definitive list of the best bands of all time, alongside high school senior photos of friends, most of whom I haven’t spoken to in years. Most of the space is taken up by a storyboard for a short film about a rocket ship that I never took further than the doors. It is the only remnant of my life there.

Now the room lives in a sort of limbo. Nana is at a care home in town, and I am halfway across the country in New York. It is neither of our rooms, and yet it is still both of ours. Mom had felt bad about replacing my things. When they first moved Nana in, she told me that it was still and always would be mine, and yet, climbing into bed the last time I visited I wasn’t entirely sure that it did belong to me. Yes, I will be welcome as long as my parents are still alive and in the house, and yes there will be no more children or parents to take in, but still the walls don’t feel the same as they do in my memory.

I have called many places home in the years since first moving away—dorm rooms, duplexes, apartments, and couches of friends and family—and yet only one remains open to my return.

Each time I visit home I feel a challenge between my memory and reality. The house is white and black now, not taupe, and there are no red bricks, and even though I know this to be true, it gives me a start. I open the front door and Winnie and Duke are not there to greet me. Of course they aren’t, and yet I feel where they should be. I feel a rush of comfort and safety. I am a young boy in my parents house. I am just learning who I might be. My bedroom is down the hall, and when I open the door I know that I will find my bed, and my sheets, and my clothes in the closet.

Now when I visit, it is mostly winter, but tucked away in my memory it is summer and I’ve opened the bedroom windows to allow the heat to push in while I lay in bed after class.

When I wake, I am in my Nana’s bed, and her night light is shining in the corner. But the chalkboard walls on my closet tell a different story. I lift my eyes and see the glow in the dark stars still stuck to the popcorn ceiling. And the dresser and blinds are still the same.

There are pockets of memory hidden all throughout the house and I find myself weaving in and out. When I look out the windows I can’t see the outside walls. So they may be white and green, or taupe and white, or white and black, or some other color that hasn’t been painted yet, but might, somewhere down the line.

New Myths For New Worlds: An Archaeologist’s Manifesto

Connor Paras Sutton

“Behold the brightness of the Sun and in the brightness of the Sun's light I depose you of your title and remove the sacred emblem of your Lordship title. I remove from your brow the deer's antlers, which was the emblem of your position and token of your nobility. I now depose you and return the antlers to the women whose heritage they are.” - from the Gayanesshagowa

Another election cycle in the U.S. approaches, and mainstream political discourse could hardly feel more stagnant. It is clear enough that all political agency rests in the hands of a few elites. Our government’s sponsorship of genocide in Palestine—a positionality totally consistent with its settler colonial and imperialist past and present—is evidence enough that the state-corporate complex operates for itself; we are little more than the objects that power it. To call ourselves a “democracy” seems a severe perversion of the notion of freedom.

Operating within the existing system will get us nowhere. What is needed are ways of thinking and acting politically that subvert the structures of violence, restriction, and exploitation that deny us the agency to create new forms of organization that are more just and sustainable for humans and non humans.

The theme of “fossils”—materials that embody within themselves stories of past realities—allows for an unexpected but profound path for reflection on what form these alternative political worlds could take. As I will argue here, the innovations in modes of thinking, being, acting, and organizing that may guide us away from the present social order will not be derived from Western political histories or an internally oriented politics. This has everything to do with the stories we tell and are told about the past. All political orders are anchored in certain time-spaces, memories, and myths, and the past few decades of archaeological research have unearthed new stories which reveal that the narratives of history that frame Western political discourse are not much more than colonizer fantasies.

This essay is split into three parts. First, I’d like to dwell more on the relation between political order, myths, and our profound, collective ignorance of non-Western political systems. We might recall that, prior to Columbus’ fateful landing on the shores of Turtle Island and the waves of genocide that followed, many millions of people were living here, organized into a diverse panorama of political systems. Might these have anything to tell us about social possibilities? This is a question that very few people in centers of power seem to ask. As we investigate why that is, I’ll demonstrate how particular stories acted on materials, bodies, and minds to animate colonial and nationalist projects around the world—especially in the 18th-20th centuries. This will put us in a better position to examine the myths which stabilize and perpetuate our own political situation in the second section. In the end, I’ll shed new light on the narratives which are emerging at the intersection of critical theory, radical politics, and archaeological research—narratives which better account for non Western social histories and Indigenous thought while prefiguring more just ways of relating to each other and to non-human aspects of the world.

MORALITY IS ANCHORED IN THE TIMES, SPACES, AND STRUCTURES OF MYTH (OR, COLONIZER CHRONOPOLITICS)

There is nothing special about the presence of stories that naturalize our political order; all groups of people tend to tell each other myths that lend order to the world and position themselves within an unraveling history.1 However, after the advent of European colonialism and the spread of nation-states, such narratives have been tightly controlled by governments. The discipline of archaeology emerged largely to bolster colonialist and nationalist narratives.

In the context of the westward expansion of the United States, settlers often came across the archaeological remains of pre-Columbian cities, earthworks, ceremonial centers, and other sites that did not accord with the narrative that cast Indigenous Americans backwards in time—as lacking complex mathematical, philosophical, or organizational capacities. These conceptions were necessary for the moral enablement of the seizure of Indigenous land and the related disintegration of Indigenous knowledge and communities. When archaeologists, prehistorians, and interested amateurs were writing in the 19th century about what had occurred in the pre-Columbian Americas, the dominant narrative—hailed by many as scientific truth—proposed that 1) over time, societies progressed through various stages of development, and 2) this process was dictated by evolutionary laws. ‘Primitive’ peoples would suffer doom, as fated by natural selection, while more advanced forms of civilization spread across the world. Europeans, according to the influential 19th century scientist John Lubbock, were the result of “intensive cultural and biological evolution,” whereas the Indigenous populations they were encountering the world over were static, unchanging.2 Only a few years after the publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species in 1859, the philosopher Herbert Spencer was employing the concept of “survival of the fittest” to argue that individual initiative fueled by self-interested behavior was the driving force of social evolution, and that capitalism would lead humanity to an earthly paradise as middle-class entrepreneurs were given the means to steer humanity further and further from its primitive state.3 This ‘social Darwinism’, we should note, was very different from biological notion of evolution. While Darwin's theory suggested a continuous branching and diversification that led to the immense variety of species in the world, social Darwinism proposed a single evolutionary path. There is one road, and it leads, unfortunately, to the capitalist empires of Europe. By trimming off all other branches, it became theoretically possible to project any given society onto a spectrum of cultural development based on their supposed ‘mastery over nature’. Many intellectuals spent their time doing exactly that.4

If we look a little deeper, it becomes apparent how, by affecting what people find important or valuable, these narratives can profoundly influence the direction that histories move.5 All such narratives are rooted in certain time-spaces; this one anchored its aesthetic quality in an idealistic memory of the Greco-Roman world—a form of ancestor worship to be sure—and counterposed the image of the European city, a space in which nature had been reduced to ornament or resource, to that of the Indigenous savage that lived close to nature or even in a ‘state of nature.’6 This myth privileged actions, behaviors, and technologies that reinforced the idea that European men were nature’s overlords. At least, this was the case for the political classes, whose power was derived from the enclosure of common lands and the dispossession of the knowledge and lifeways of the peasants, natives, and women who would become the unwilling reproductive force of capital.7 The rhetoric of Israeli politicians that casts Palestinians as “human animals,” unproductively taking up space in land with great economic potential, reveals the persistence of this masters-of-nature/savages-within-nature dichotomy into the present.8 One could argue it is a necessary foundation to capitalist expropriation anywhere. My point here is that narratives of the past—as they inevitably intertwine with morality, aesthetics, politics, and ways of knowing and being in the world—prefigure certain kinds of futures.

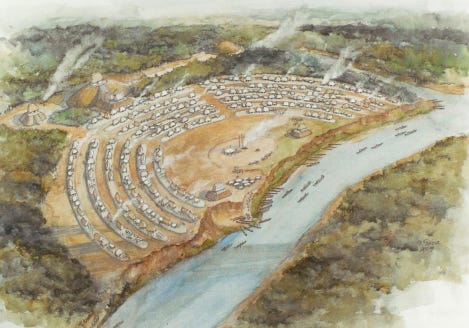

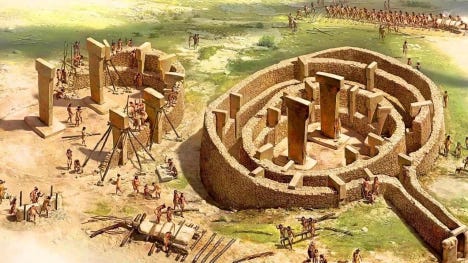

Now let’s return to the 19th century intellectuals writing about the pre-Columbian Americas. As they were confronted with archaeological evidence that indicated ancient groups of American hunter-gatherers were transforming vast landscapes and constructing monumental centers, these writers tended to speculate that such works were left by ancient giants, lost tribes of Israel, or a race of white people who had since perished, likely at the hands of the ‘primitive and warlike’ Indians.9 This was the case for sites like Poverty Point, in modern-day Louisiana, in which over 750,000 cubic meters of earth were moved to form a ceremonial infrastructure that we now understand to have been occupied by seasonal congregations of hunter-gatherers over 3,500 years ago.10 The construction of Poverty Point, with its architectural alignments to celestial north and the summer and winter solstices, reveals a deep understanding of mathematics, geometry, and astronomy, as well as an interest in the movements and mechanics of the cosmos.11 What social and political dynamics were at play as many thousands of hunter-gatherers congregated in tiny cities at particular times of the year, engaging in massive feats of collective labor and effectively creating and then dismantling new kinds of societies on a seasonal basis? Prior to the last few decades, such questions have hardly been posed.12

Rejections of the creative and intellectual capacity of Indigenous groups were essential to the myths that supported colonial expansion in all corners of the world. In South Africa, the ruins of the medieval Bantu city of Great Zimbabwe were interpreted by archaeologists to be the remains of an ancient Phoenician colony or some otherwise ‘northern race’ that had visited southern Africa in biblical times; Great Zimbabwe thus became “a symbol of the justice of European colonization, which was portrayed as the white race returning to a land that it had formerly controlled.” In India, too, as ancient Buddhist and Hindu sites were revealed to Western eyes, British colonization was presented as rescuing India from the decline it had suffered since a previous Golden Age.13 Such was the White Man’s Burden. These narratives do more than render certain political actions and organizations acceptable in a static moral system. Rather, they meld together particular times, places, memories, aesthetics, political forms, and values in a process that alters and is altered by notions of what is moral. Archaeological sites are thus reconstructed and repurposed in cultural imaginaries by these political-historical myths; they become the places “where the knots of narrative are tied and untied.”14

We can see similar processes at work in the myths that were employed to bring nation-states into existence—that is, to instill a shared sense of history and identity in populations somewhat arbitrarily grouped together and set off from others by the creation of territorial boundaries. In Franco’s Spain (ca. 1939-1975), the state narrative identified modern Spaniards as descendants of Celtic groups who had, in the long-term, succeeded in marginalizing the Jewish and African elements of the population; in doing so, it homogenized a range of ethnic groups with diverse histories, in part by setting them off against vilified Jews and Africans, while indicating that the arc of history bent in the Spanish subject’s favor through the ascendancy of the nation-state of Spain. After the forced unification of Italy in the mid-19th century, a new elite threw their support behind an emerging (and unsubstantiated) archaeological theory which proposed that Bronze Age Italy was colonized by waves of northern populations who, replacing Neolithic natives, established a Latin cultural unity across the peninsula. A few generations later, Italy’s mainstream historical narrative shifted in the context of Mussolini’s vision of an expansive, fascist state; history was re-centered in Rome as the new regime presented itself as the Roman empire reincarnate (Mussolini himself was photographed delivering the first blow of a pickaxe in excavations of the Roman Forum). The Nazis infamously had their own archaeological researchers that sought to demonstrate the cultural superiority of Germanic peoples, who had supposedly occupied a great deal of Europe in a pre-historic age—it was, therefore, a moral imperative of the Nazi party to reintegrate this ancestral fatherland. In response, the Soviet Union, threatened by an expanding Nazi Germany, sponsored archaeologists to demonstrate that Slavic culture was older and more developed than German culture.

More recently, Zionist archaeology—a nationalist rather than religious project—has taken the biblical era as its sole epoch of interest to strengthen the link between the Israeli state and the land it occupies. Archaeology has had a particularly central role in realizing Zionist ambitions. Through the act of excavation, archaeologists have been digging past layers of continuous occupation by Palestinians, carving biblical-era sites and settlements out of the earth in order to literally remake the landscape to fit a Zionist image.15 This act appears to project the Israeli state into the deep-past, bringing the histories of ancient Hebrews into view while leaving no space in time for the people who have lived there in all the epochs in-between. It is no coincidence that the most prominent Israeli archaeologist of the 20th century—Yigael Yadin, famous for his highly publicized excavations at Masada and his work on translating the Dead Sea Scrolls—was a former chief of staff of the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) and was quite self-consciously intending to produce myths that romanticized the Zionist project.16 These myths were necessary for the creation of the new subjects of the Israeli state:

The new Hebrew/Israeli person was imagined as secular/modern as opposed to religious/traditional, active as opposed to passive, and connected to the land, as a laborer, as opposed to disconnected from it, most fundamentally, as a diasporic person. Rejecting the "religious way of life" of the Jewish Diaspora, that is, the "culture of the book," the new Hebrew would, ideally, be fashioned in and through a connection to the land. . . . “Making place” or territorial “self-fashioning,” to borrow Stephen Greenblatt’s phrase, emerged as a pivotal dimension of that political project of Labor Zionism, which involved not only the creation of a new Hebrew subject or citizen, but, moreover, the remaking of the land itself.17

This redefinition of Palestinian land—which involves the destruction or renaming of Indigenous sites to eliminate the memories they materialize—could be seen as a slow and subtle contribution to the ongoing act of genocide perpetrated by Israel’s settler-colonial regime. The annihilation of Palestinian places and people with bombs and missiles is a hyper-concentration of the same activity: the erasure of a people out of time, space, and memory. Landscapes are full of stories; deathscapes tell only of loss.

What should be clear from these examples is the power myths have to configure morality, identity, and political discourse, and that governments have been in the habit of controlling these narratives for the past few centuries. It is also important to note that embedding historical consciousness in certain times, places, and stories is always as much about forgetting as it is about remembering.18 In Israel, anchoring memories of the past in the biblical era removes Palestinians from history. “There is no Palestinian history,” claimed the Israeli Minister of Finance, Bezalel Smotrich, at a speech in Paris in 2023. In Africa and the U.S., historical narratives were drafted by colonizers to study the Indigenous past in a manner that denied the past included Indigenous peoples at all, often coming up with bizarre and fantastical scenarios to do so. In the next section, we will see how our memories—and, consequently, our representations of the world—are still severely damaged by similar narratives.

SETTING A TORCH TO MIDDLE-CLASS EPISTEMOLOGIES (AND CLEARING THE WAY FOR SOMETHING NEW)

Not many people in the U.S. today would take seriously the notion that pre-Columbian archaeological sites were the work of giants or a lost race of Europeans. Our understandings of what has occurred through time and space have been reconfigured in a manner that largely rules out such possibilities. However, the stories that are told or are implicit in political discourse, media, and classrooms from the elementary school to the university still do the work of forgetting non-Western pasts and enforcing middle-class epistemologies—that is, ways of knowing and relating to the world that naturalize colonial projects, wealth disparities, and extractive relationships. On the one hand, they provide a myth of optimism for comfortable people; on the other, a hopeless fatalism for less secure people. Even the most well-meaning among us may suffer from a sort of “unconscious manifest destiny.”19 When unconfronted, these narratives dissolve contingent hierarchies, inequalities, and structures of violence into the very fabric of the world. Let’s examine a couple of popular versions.20

Myth 1: For the vast majority of human history, life was “nasty, brutish, and short.” Resources were scarce, and violence was the optimal strategy for survival. People lived, for the most part, in a war of all against all. Then, sometime within the last 12,000 years, the Agricultural Revolution occurred. There were surpluses for the first time in human history. The men who seized control of surpluses established themselves as sources of order against the previous chaos of social existence; war was diminished, private property became the basis of civilized life, and inequality was a non-issue as all classes of people were continually raised from the primitive condition. Villages became cities, and cities required central governments to administer these increasingly complex networks of people, things, and information. Police forces became necessary to maintain internal order, armies to secure society from external forces—before you know it, kingdoms, empires, and then nation-states are everywhere. Progress towards prosperity defines the arc of history. This was inevitable.

Myth 2: For the vast majority of human history, people roamed about in small bands of hunter gatherers, living relaxed but relatively simple lives. Then, sometime within the last 12,000 years, the Agricultural Revolution occurred. There were surpluses for the first time in human history. Groups of strongmen, greedy at the chance to reap the benefits of others’ work without investing any time themselves, violently secured control over reserves and started setting up armies to defend themselves—war, patriarchy, and private property were created in the same stroke. Meanwhile, surplus food allowed for extreme population growth. The men who seized control of surpluses established themselves as a divinely warranted ruling class, exploiting, enslaving, and expanding their subject populations. Villages became cities, and cities required central governments to administer these increasingly complex networks of people, things, and information. Police forces became necessary to maintain internal order, armies to secure society from external forces—before you know it, kingdoms, empires, and then nation-states are everywhere. Inequality and patriarchy are the price of civilization. This was inevitable.

Both myths are espoused directly by various popular writers. The first, most common amongst conservatives and elites and closer to what is taught in school curricula, describes the position of thinkers like the psychologist and popular science writer Steven Pinker in The Better Angels of Our Nature or Enlightenment Now, which essentially argue that we owe our reason, “equality”, and tolerance of one another to the Great Men of the Enlightenment. (What little value Pinker’s ideas may have had seems to be decaying fast as recent studies increasingly show how much the ideas of Enlightenment political philosophers were inspired by missionary accounts of Indigenous political orders on the frontiers of settler-colonies, but I can’t dive too deeply into all that here.21) The second myth is more or less the grand narrative of history presented by Yuval Noah Harari in Sapiens; it is generally espoused by the sort of leftists who are deeply embedded in the current state of affairs and probably not interested in shaking up the political order (official marketing for Sapiens, for example, notes the book’s placement on the summer reading lists of Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, and Barack Obama). Structurally, it is almost identical to one of the more ancient grand narratives of the human past—the biblical Fall from Grace. Once, both stories begin, we lived in relative ease and prosperity. The temptation presented by a certain plant—the Apple in the Garden of Eden, or wheat in the Neolithic Fertile Crescent—lured humanity into a trap we cannot escape. We now inhabit worlds rife with pain, toil, and inequality, and we are doomed to inhabit this state as long as we remain on Earth.22

For present purposes, what’s important about these myths are their commonalities. They are clearly inversions of each other, sharing a similar structure but moving in opposite directions. Both are unilineal; i.e., they present a single path that links our pre-agricultural ancestors to our present situation, whether our ancestors are imagined to be easy-going egalitarians or violent savages.

Implicit, then, in both myths is the idea that we are at an unprecedented pinnacle of development (whether or not that’s a good or bad thing), and that every society that has ever existed could be placed at some point along this path that leads to our present situation. In this way, they are continuous with the social Darwinism of previous centuries. A logical consequence of such an idea is that other (non-Western) modes of organization cannot tell us anything new or unanticipated about social possibilities. At best, the Indigenous outsider can lob naïve critiques from a superseded and no-longer-relevant stage of development: the wise, respectable, but ultimately barren words of the noble savage.

In fact, the last few decades of research have revealed that both myths are wrong at just about every level. At best, their opposite trajectories capture the ambivalence of people absorbed into the amorphous social-historical entity that is ‘the West’ about its history. As soon as one tries to fit actual histories into these narratives, they fall to pieces.

Hunters, Gatherers, Foragers, Fishers

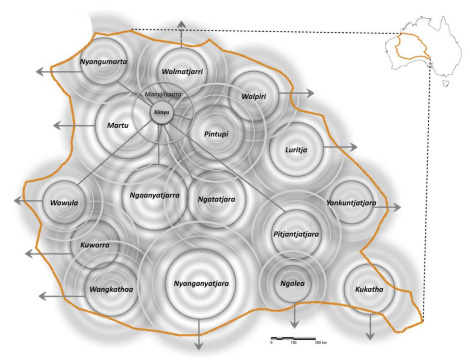

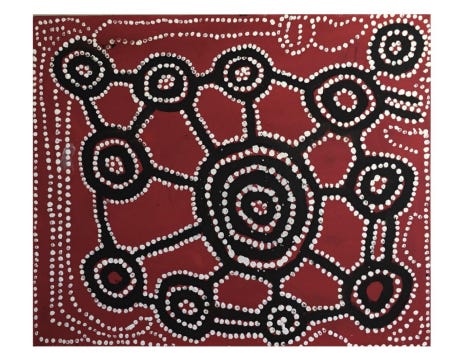

Let’s start with pre-agricultural peoples—were they engaged in a perennial war of all-against-all, or were they roaming around in small bands of easy-going simpletons? It turns out that trying to characterize some 200,000 years of social existence as one way or another was never a good approach. Anthropological research on all continents has made it clear that there never were static, isolated bands of hunter-gatherers. The organization of hunter-gatherer groups is, as a rule, dynamic; individuals may engage in the activities of foraging, crafting, ritual, and sitting by the hearth in the evening with entirely different groups of people—groups that vary in scale and structure, drawn from larger social networks.23 Systems of ‘classificatory kinship’—what we might call ‘chosen families’—tend to be much more significant than biological relations in such contexts. Further, it is extremely common to find hunter-gatherers with crafts or rare materials from hundreds of miles away. These materials moved as groups shared rituals, knowledge, technology, games, music, and images that formed the bases of social networks that spanned continents. In the Western Desert of Australia, for example, it is shared access to religious knowledge, performances, and paraphernalia that tie people together across hundreds of thousands of square kilometers. For Indigenous Australians, these sprawling religious communities function as networks of security and hospitality: “because far flung acquaintances can be made family, no matter where you go you have family to live and work with.”24

On occasion, these vast constellations of hunting-and-gathering groups all over the world would coalesce into seasonal ‘mega-sites’, such as Dolní Vě stonice, Göbekli Tepe, or Stonehenge, in which an entirely different social order came into being. As with the hunter-gatherer groups that constructed Poverty Point, social organization generally appears to have been fluid, morphing to the rhythms of seasonal variations in climate, flora, and fauna.25 Now we can search for an answer to our earlier question—what are the political implications of social orders which can be built-up and taken-down on a seasonal basis? More recent instances of this seasonal dynamism fill the picture with color.

In the Great Plains of North America, for example, seasonal congregations of hunting-and-gathering groups built up structures of coercive authority which inverted their otherwise steadfast value of individual autonomy:

The equalitarian attitudes of everyday life recede, supplanted by a transitory over- lordship. Omaha captains even appointed policemen who had the right to beat refractory or lagging warriors... About 1820 the Cheyenne conceived themselves as one huge war- party, whose leader thus automatically became supreme, supplanting the tribal council of "chiefs." Yet in consonance with native ideology he retained not a vestige of his special authority when his task was done.26

The last point is especially important—authoritative power was bestowed for the season or occasion, only to be completely revoked at season’s end:

...the Plains Indians were conscious political actors, keenly aware of the possibilities and dangers of authoritarian power. Not only did they dismantle all means of exercising coercive authority the moment the ritual season was over, they were also careful to rotate which clan or warrior clubs got to wield it: anyone holding sovereignty one year would be subject to the authority of others in the next.27

Here, we see one consequence of seasonally transforming societies: it is difficult to establish any permanent hierarchies, inequalities, or structures of violence—especially if those you have power over this summer will be ordering you around next summer. But the case of the Great Plains is just one example among an irreducible diversity. Consider the following summary from a recent study comparing seasonal dynamics in the Great Plains, Central Brazil, and the Northwest Coast of America:

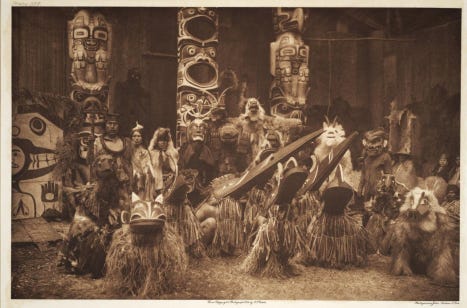

The societies of the Great Plains created structures of coercive authority that lasted throughout the entire season of hunting and the rituals that followed, dissolving when they dispersed into smaller groups. Those of Central Brazil, by contrast, dispersed into foraging bands [during the dry season] as a way of asserting a patriarchal authority that was ineffectual in village settings [of the wet season]. And the Kwakiutl of the Northwest Coast explored still other possibilities, granting effective police powers to performers in the Midwinter Ceremonial (the “bear dancers” and “fool dancers”) that could be exercised only during the performance of the ritual itself.28

Our first takeaway from these examples should be that we cannot presume to know everything about the way a group of people are organized just because they derive their food from hunting and gathering. While we don’t have the space to explore them here, each of the cases listed above—the Great Plains, Central Brazil, and the Northwest Coast—all have their own political histories, with social dynamics that change through time in response to fluctuations in what people find valuable, moral, practical, or desirable. Further, with similarly seasonal dynamics of social transformation being present in the organization of our non-agricultural ancestors, it is clear that there is no original, ‘natural’ state of war, peace, hierarchy, or equality from which we have been permanently severed. Rather, it appears that much of humanity has spent its time self-consciously sliding up, down, in, and out of the spectrum of cultural development that, according to Western notions of historical process, is supposed to move in only one direction and lead, inevitably, to the nation-state.

Agriculture

But did agricultural irreversibly eliminate the possibly of experimenting with alternative political orders? Firstly, the term ‘Agricultural Revolution’ creates a picture of a rapid and totalizing transformation in food production and social organization that never actually happened. The ‘Agricultural Revolution’ encapsulates several thousands of years of experimentation in gardening, biology, medicine, herbology, and fiber technologies in addition to food production that unraveled independently in such a variety of places as the Andes, Mesoamerica, West Africa, the Pacific Islands, Egypt, Mesopotamia, India, China, and the eastern woodlands of North America. It is certainly true that our current geopolitical situation, with nation-states covering the globe, could not exist without cereal-based agriculture, but the diversity in expressions of agriculture and its relation to social organization, as exemplified in the histories of the different places listed above, render it impossible to argue that agriculture necessarily leads to the state, patriarchy, or wealth disparities.

Rather than blindly creating the means for permanent structures of exploitation and inequality, evidence indicates that people explored cautiously how different relations with land and sources of food enabled or restricted certain forms of social organization. In Southeast Asia, for example, agriculture proceeded for some 6,000 years before any states emerged, and even then states occupied marginal and ephemeral positions in the social landscape.29 Presumably, people did not spend all that time waiting for the state to be built over their heads—rather, they developed ways of organizing agricultural societies without the need for police, armies, or centers of control. In farming societies all around the world, complex systems of communal land-sharing prevented relations of extreme inequality from Peru to Russia until colonial violence imposed more capitalistic relations in their stead. The ‘Tragedy of the Commons’ is nothing more than a colonizer fantasy—one that has been frequently cited by governments as they abolish commons and transfer ownership of land to individuals and corporations.30 What has happened since the latter became the stewards of the earth speaks for itself.

In the eastern woodlands of North America, the agricultural society of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, also known as the Iroquois, was and remains a union of the Mohawk (Kanien’kehaka), Oneida (Onayotekaono), Onondaga (Onundagaono), Cayuga (Guyohkohnyoh), Seneca (Onondowagah), and Tuscarora (Skaruhreh). Their political constitution—the Gayanesshagowa, or Great Law of Peace—narrates the adventures of culture heroes who combat the coercive authority of the witch-king Tadodaho. As they bring all people together to overcome the witch’s despotic power, they elaborate a system in which “titles, nested councils, consensus-finding, condolence rituals, and the prominent role of female elders” formalize the political structure of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy.31 It is a striking example of how story, morality, and political order can be self- consciously woven together to create a certain kind of society. The legal aspect of the Gayanesshagowa—which predates Columbus’ footfalls on Turtle Island—lent its form and structure to the U.S. Constitution, while women’s autonomy in Haudenosaunee society stimulated 19th century feminists.32 Further, the creators of the Great Law recognized that any sort of political constitution which is set in stone and held together by violence when it might otherwise fall apart (e.g., deploying police against one’s citizenry when they start exercising a little too much ‘free speech’), will not need to be constantly maintained, reproduced, kept living:

Every five years the Five Nations Confederate Lords and the people shall assemble together and shall ask one another if their minds are still in the same spirit of unity for the Great Binding Law and if any of the Five Nations shall not pledge continuance and steadfastness to the pledge of unity then the Great Binding Law shall dissolve.33

Here is an understanding that social order, like any healthy relationship, must be reflected upon, reconfigured, and sometimes dismantled and put back together in new forms.

In short, the necessary or inevitable evils that pervade modern societies were never necessary or inevitable, and, in fact, a great number of social institutions were devised across the world to avoid them. Agriculture was not our Fall from Grace. If these alternative ways of organizing have largely disappeared today, it is the result of the tremendous amount of violence involved in colonial domination and the casting of all corners of the world into the mold of the nation-state.

Urbanism

Finally, archaeological evidence makes it very apparent that urbanization does not necessitate structures of violence (i.e., police, prisons, and armies) to maintain order. Nor is it the case that cities always lead to class formation or state development.34 Comparative studies of urbanism in archaeology are revealing “cities that may have consisted of dispersed settlement mounds without a central core; cities that lacked kings, courts, palaces, and state religions; cities whose residents created systems and structures for leadership, administration, and international relations that were dispersed among diverse interlocking groups, rather than under singular linear systems of rule.”35 The reasons for urbanizing in different contexts seem quite particular and difficult to generalize, but in any case, the city presents a social landscape that affords new ways to structure families and communities; participate in festivals, rituals, and religious activities; and engage in new forms of art, architecture, craft, cuisine, and performance.36 These myriad potentials were tapped in a variety of ways across the world.

In the urban age of the Indus Valley civilization (2600-1900 BC), a network of thousands of settlements, including cities like Mohenjo-daro, Harappa, Dholavira, and many others, operated without central governments, wealth inequalities, or evidence of warfare. At Mohenjo-daro, for example, the resident population of at least 40,000 were all housed in complexes that contained courtyards, wells, and hearths, and were integrated in an “intricate system of drainage pipes that allowed each structure to have a private bathing platform.”37 Across the Indus Valley, intricate, multi- stage, and deeply complex technologies and processes of craft production were known from the city to the farm, indicating that the sharing of knowledge and technique across social boundaries was valued over restriction and differentiation.

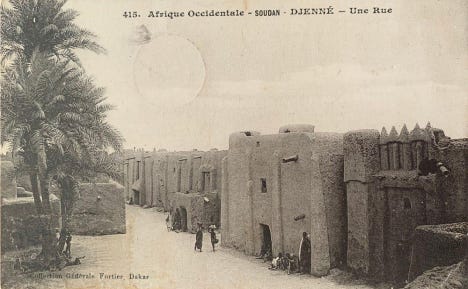

Across the Pacific Ocean, something like a few hundred-thousand people inhabiting the densely populated and geographically constrained river valleys of the north coast of Peru in the first millenium AD were organized into a series of cities and rural hinterlands, sustained by advanced irrigation and agricultural technologies as well as the rich fisheries of the Pacific coast. For hundreds of years, they existed without any sort of overarching governing apparatus. Instead, this deeply complex and ever-shifting social landscape was characterized by the individual autonomy of local groups, expressed through idiosyncratic art styles and settlement patterns, as well as a fluid mode of organization that allowed for cyclical or permanent transformations in social structure without friction or eruptions of violence.38 Similarly, the cities that comprise the urban clusters of Jenne-jeno (300 BC–1200 AD) in West Africa were characterized by “networks of horizontal relations among diverse, economically specialized, corporate groups [that] created an urban system based on multiple and complex relations of reciprocity shaped within a widely understood ‘social contract.’”39 In general, as urbanism and social organization in Africa’s past are increasingly understand, the role of “creativity and consent” as opposed to “conquest and coercion” in the (re)production of social relations are being emphasized in ways that have been totally unanticipated by Western political philosophy.40

We might also turn to the Valley of Mexico, the site of some of the largest cities in the pre-modern world, where images of spectacular ritual sacrifice and massive empires have often overshadowed a parallel tradition of egalitarian cities like Tlaxcala, whose ethos was materialized in decentralized neighborhoods, a focus on accessible public amenities, and a large, rotating council of politicians who were subject to rituals of humiliation by the public. Through a series of ‘Flower Wars’, Tlaxcala managed to remain independent from the empire of the Aztec triple-alliance, in part because its population was bolstered by the “political dissidents and uprooted families fleeing imperial control and warfare” who made this outpost of freedom their home.41

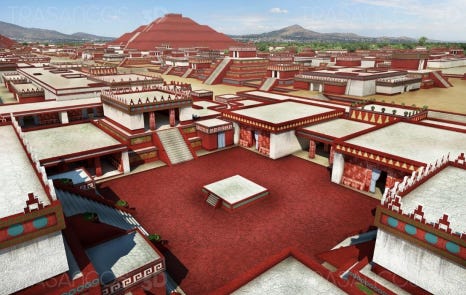

It is hard to head out into the nightmare landscape that is our mazes of strip malls, fast food chains, gentrified apartments towering over the unhoused, and the eerie homogenies where our suburban overlords dwell without feeling a twinge of jealousy for the painted and decorated cohousing compounds of Teotihuacan, a multiethnic city without kings in which at least 90% of a population of ~100,000 were housed in what archaeologists first thought were palaces.42 In the end, this exploration is not about “digging for utopia”—it is about expanding our capacity to imagine what cities can be.43 From the low-density, “garden urbanism” of Mesoamerica, Amazonia, or Cambodian Angkor; to the seasonally occupied sites of ritual convergence like the Inka capital of Cuzco; or the dense and perennially occupied landscapes of Rome and Mohenjo-daro, there is no inevitable trajectory we are doomed to follow once large groups of people start living together.44

Now the mask is off. Every layer of our universalizing metastructure of historical change is revealed to be the projection of a myth designed to eliminate all color from non-Western social histories, supposed to be degenerate forms of our own. The stories that give form to ‘common-sense’ assumptions about what is natural, moral, reasonable, and possible are revealed to be what they have always been: the tools of colonizer, with which he has built walls in our minds.

THE MOST RADICAL STORIES ARE IN THE DIRT

If the immense variety of social systems that have proliferated across time and space are not simply so many different cultural reflections of the same few, derivative structures repeating themselves over and over, then it stands that we are closing ourselves off to worlds of profound social possibilities by isolating political discourse within a narrative that assumes there is nothing worth learning outside of the Western tradition. It is unthinkable that establishment politicians will start referring to Indigenous political histories to indicate new potential ways of organizing; it would subvert the colonial project of which they are a part.

If, as we have said, anchoring our ideas of history in certain times, spaces, and structures entails forgetting as much as remembering, we are encouraged to be cautious about what we desire to remember and what we are prepared to forget. The selection of fossils we might weave together to craft new stories that prefigure more just forms of social existence is a delicate act; a volatile art. It demands the creativity facilitated by exposure to a diversity of social worlds. As the Black Trowel Collective—a group of academic, anarchist archaeologists—has recently expressed, these worlds are the subjects of stories that the underlayers of the earth might tell us, if we care to listen:

The archaeological record is fundamentally a record of cooperative human, and indeed nonhuman, endeavors. Nothing that exists from the human past came about as a result of isolated individual genius or initiative but rather emerged from constellations of flexible, creative, and collaborating people... If there is any unifying feature of humanity (or indeed of hominins more broadly), it is our creativity.45

Ultimately, this essay is a call for consideration of alternative ways of knowing, being, and organizing as we think and act on creating new kinds of social and political relations—an activity that will become increasingly necessary as the current world system devours its own body. This is important political work—failing to recognize the contingency and arbitrariness of exploitative social relations will inevitably result in their reproduction. It will, however, be necessary to go further than identifying and tracing lineages of exploitation; most of us already recognize that things are bad enough to demand urgent and dramatic change. Going beyond criticism and starting to catch glimpses of radically alternative social worlds can start with serious consideration of non-Western political forms. What these glimpses make clear is that our relationships with each other, land, animals, and other non-human aspects of the earth do not have to be what colonizers have made them; other worlds are possible. So many, in fact, rest in the dirt just beneath us.

References

Abu El-Haj, Nadia. 2002 Facts on the Ground: Archaeological Practice and Territorial Self- Fashioning in Israeli Society. University of Chicago Press. Bakhtin, M. M. [1975] 1981 The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Trans., Michael Holquist, and Caryl Emerson. University of Texas Press Slavic series. Austin: University of Texas Press. Bird, Douglas W., Rebecca Bliege Bird, Brian F. Codding, and David W. Zeanah. 2019 "Variability in the organization and size of hunter-gatherer groups: Foragers do not live in small-scale societies." Journal of Human Evolution 131: 96-108. Borck, Lewis. 2018 "Constructing the Future History: Prefiguration as Historical Epistemology and the Chronopolitics of Archaeology." Journal of Contemporary Archaeology 5 (2): 229-238. Black-Trowel Collective, Marian Berihuete Azorín, Chelsea Blackmore, Lewis Borck, James Flexner, Catherine Frieman, Corey Herrmann, and Rachael Kiddey. 2023 "Archaeology in 2022: Counter‐myths for hopeful futures." American Anthropologist 126. Descola, Philippe 2013 Beyond Nature and Culture. Paperback edition ed. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Trans. Janet Lloyd. Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne. 2014 An indigenous peoples' history of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press. Fargher, Lane F., Richard E. Blanton, and Verenice Y. Heredia Espinoza. 2010 "Egalitarian Ideology and Political Power in Prehispanic Central Mexico: The Case of Tlaxcallan." Latin American Antiquity 21 (3): 227-251. Fargher, Lane F, Richard E Blanton, Verenice Y Heredia Espinoza, John Millhauser, Nezahualcoyotl Xiuhtecutli, and Lisa Overholtzer. 2011 "Tlaxcallan: the archaeology of an ancient republic in the New World." Antiquity 85 (327): 172-186. Federici, Silvia. 2004 Caliban and the Witch. New York, London: Autonomedia. Graeber, David. 2001 Toward an Anthropological Theory of Value: The False Coin of Our Own Dreams. New York: Palgrave. Graeber, David, and David Wengrow. 2021 The Dawn of Everything: a New History of Humanity. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Green, Adam S. 2021 "Killing the Priest-King: Addressing Egalitarianism in the Indus Civilization." Journal of Archaeological Research 29 (2): 153-202. Jennings, Justin, and Timothy K. Earle. 2016 "Urbanization, State Formation, and Cooperation: A Reappraisal." Current Anthropology 57 (4): 474-493. Johansen, Bruce E., and Barbara Alice Mann. 2000 Encyclopedia of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy). Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. Kidder, Tristram R. 2012 "Poverty Point." In The Oxford Handbook of North American Archaeology, edited by Timothy R. Pauketat, 460-470. Oxford University Press. Lowie, Robert H. 1948 "Some Aspects of Political Organization Among the American Aborigines." The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 78 (1/2): 11-24. MacGaffey, Wyatt. 2003 "Crossing the River: Myth and Movement in Central Africa." Angola on the Move: Transport Routes, Communication, and History, Berlin. Mann, Charles C. 2005 1491: New Revelations of the Americas before Columbus. Knopf. Manzanilla, Linda R. 2015 “Cooperation and tensions in multi-ethnic corporate societies using Teotihuacan, Central Mexico, as a case study.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112 (30): 9210–15. McIntosh Roderick J. 2015 Different cities: Jenne-jeno and African urbanism. In: Yoffee N, ed. The Cambridge World History. Cambridge University Press: 364-380. Murray, Calum. 2022 "John Locke's Theory of Property, and the Dispossession of Indigenous Peoples in the Settler-Colony," American Indian Law Journal: Vol. 10: Iss. 1, Article 4. Parker, John. 2023 "Kings, Kingship, and Kingdoms in African History." In Great Kingdoms of Africa, edited by John Parker, 11-27. University of California Press. Ortmann, Anthony L., and Tristram R. Kidder. 2013 "Building Mound A at Poverty Point, Louisiana: Monumental Public Architecture, Ritual Practice, and Implications for Hunter-Gatherer Complexity." Geoarchaeology 28 (1): 66-86. Quilter, Jeffrey, and Michele L. Koons 2012 "THE FALL OF THE MOCHE: A CRITIQUE OF CLAIMS FOR SOUTH AMERICA'S FIRST STATE." Latin American Antiquity 23 (2): 127-143. Radkau, Joachim. 2008 Nature and Power: A Global History of the Environment. Cambridge University Press. Romain, William F. and Normal L. Davis. 2014 “Astronomy and Geometry at Poverty Point.” Louisiana Archaeology: 38. Rostain, Stéphen, Antoine Dorison, Geoffroy de Saulieu, Heiko Prümers, Jean-Luc Le Pennec, Fernando Mejía Mejía, Ana Maritza Freire, Jaime R. Pagán-Jiménez, and Philippe Descola. 2024 "Two thousand years of garden urbanism in the Upper Amazon." Science 383 (6679): 183-189. Said, Edward. 1978 Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books. Scott, James C. 2017 Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States. Yale University Press. Silberman, Neil Asher. 1993 A Prophet from Amongst You: The Life of Yigael Yadin: Soldier, Scholar, and Mythmaker of Modern Israel. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Pub. Co. Sinopoli, Carla. M., Roderick J. McIntosh, Ian Morris, and Alex R. Knodell 2015 The distribution of power: hierarchy and its discontents. In N. Yoffee (Ed.), The Cambridge World History: 381–394. Cambridge University Press. Smith, Michael E., Abhishek Chatterjee, Angela C. Huster, Sierra Stewart, and Marion Forest. 2019 "APARTMENT COMPOUNDS, HOUSEHOLDS, AND POPULATION IN THE ANCIENT CITY OF TEOTIHUACAN, MEXICO." Ancient Mesoamerica 30 (3): 399-418. Spivey, Margaret S., Tristram R. Kidder, Anthony L. Ortmann, and Lee J. Arco. 2015 "Pilgrimage to Poverty Point?" In The Archaeology of Events: Cultural Change and Continuity in the Pre-Columbian Southeast, edited by Zackary I. Gilmore and Jason M. O'Donoughue, 141-159. The University of Alabama Press. Swenson, Edward. 2007 "Adaptive strategies or ideological innovations? Interpreting sociopolitical developments in the Jequetepeque Valley of Peru during the Late Moche Period." Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 26 (2): 253-282. 2019 “The Mutable Neighborhoods of the Late Moche Period in the Jequetepeque Valley, Peru." Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association 30 (1): 100-113. 2021 "City, State, and Market: Lessons from Mesoamerica." Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association 32 (1): 179-188. Trigger, Bruce G. 2006 A History of Archaeological Thought. 2 ed. Cambridge University Press. Walmsley, Peter. 2023 "Locke Among the Wendat." Eighteenth - Century Studies 56 (2): 213-219. Wengrow, David. 2015 Cities before the State in Early Eurasia: Goody Lecture. Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, Department ‘Resilience and Transformation in Eurasia’. 2018 The Origins of Civic Life - a Global Perspective. Origini, 42, 25-44. 2024 On historical materialism and ‘The Dawn of Everything’. Contemporary Political Theory. Wengrow, David, and David Graeber. 2015 "Farewell to the ‘childhood of man’: ritual, seasonality, and the origins of inequality." Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 21 (3): 597-619.

The Empire Rears Its Ugly Head At The DMV

Sebastian Hagelstein

CHARACTERS

PHIL/THOMAS: Bearded man in his 40s

PAUL/LUCIUS: Man, any age

TESS/TULLIA: Woman, late 20s-early 40s

SUSAN: Woman, 20s-30s

EMPLOYEE: (Voice Only)

Fullerton, CA. Three people stand in line at the drab fluorescent purgatory known as the Department of Motor Vehicles. PHIL, his wife TESS, and PAUL in line ahead of them. Every once in a while a DMV EMPLOYEE calls ‘NEXT,’ and everyone shuffles forward a little across the stage, indicating they are in a long, slow-moving line. The DMV employee is a disembodied authoritarian voice from above. Phil speaks to Tess: